1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Ethiopia is one of the two African states not colonized by European powers. Supported by the Europeans, the Abyssinians conquered neighbouring peoples such as the Oromos, Sidama, Somali, and others to form the present state of Ethiopia through internal colonialism (Dugassa 2021; Holcomb and Ibssa 1990). Despite being a founding member of the United Nations and a signatory to its charters, Ethiopia did not allow the Oromo people to freely exercise their right to self-determination, highlighting the lasting impact of colonialism on the indigenous Oromo people’s rights (Dugassa 2021). The historical context of the Oromo people’s struggle, their intent to exercise the right to self-rule, and the Ethiopian government’s determination to maintain the colonial social structure led the region to conflict and instability. The Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) insurgency and the Ethiopian government’s scorched-earth counterinsurgency tactics have occurred in this context.

The main aim of this article is to describe features of the Government of Ethiopia’s (GoE’s) violent counter-insurgency approach in Western Oromia, specifically in the four Wollega zones of Kellem Wollega, East Wollega, West Wollega, and Horru Guduru Wollega. Wollega is located in the Western part of Ethiopia, and its population has historically been known for its rich agricultural economy, primarily based on farming, coffee production, and livestock rearing (Jalata 2023a). The Oromo people in Wollega are part of the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, the Oromo, which constitutes over 40% of the country’s population. Wollega borders three of Ethiopia’s regional states: Amhara, Benishangul-Gumuz, and Gambella, as well as the Upper Nile state in South Sudan. It holds significant cultural importance for the Oromo people, serving as a stronghold of their language, Afaan Oromoo, and their Gadaa system, an indigenous socio-political governance structure.

Politically, Wollega has been the center of Oromo nationalist movements, including the Oromo Liberation Army-Oromo Liberation Front (OLA-OLF), which struggled for greater autonomy and self-determination for the Oromo people. This region produced the founders of the Oromo national movement and leaders like Baro Tumsa and Abiyu Geleta, who articulated the aspirations of the Oromo people. The ideological constructs of the Oromo national movement, which advocated for the right to self-determination, which includes self-rule in a federation, confederation, or independence, were born in this region (Jalata 2023a). These constructs, which formed the backbone of the movement’s goals and strategies, were collectively accused by the successive Ethiopian regimes of being anti-Ethiopian. These aims and goals conflicted with the policies of the successive Ethiopian governments, which perpetuated and benefited from structural inequality and kept the Oromo on the economic-political periphery.

1.2. Problem Statement

The conflict and displacement crisis in Oromia Regional State in Ethiopia barely makes the national and international news and humanitarian headlines. In its latest report, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) noted:

“Oromia doesn’t make the headlines, yet civilians continue to be deeply affected by violence, with many people killed or injured and limited help coming from outside the region” (ICRC 2024)

Since 2018, Oromia National Regional State (ONRS), Ethiopia’s most significant region, has faced insurgency and counterinsurgency (COIN) operations. It erupted after a reconciliation agreement reached in August 2018 between the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and the GoE collapsed. Presumably, the agreement aimed to pave the way for the return of the OLF to Ethiopia, disarm its fighters, and engage in peaceful opposition politics. However, an organized disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) program did not occur, due to which the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), the armed wing of the OLF, returned to armed struggle to fight for the Oromo people’s right to self-determination, under the leadership of Jaal Marroo from its base in Wollega, Western Oromia (Wudeneh Chemeda 2024; Jalata 2023b). This led to a complex and brutal counter-insurgency operation.

There are two contrasting approaches to understanding counterinsurgency: enemy-centric and population-centric. In the former, the primary task of counterinsurgency is defeating the enemy at all costs (Paul et al. 2016, 26). This approach entailed the “first defeat the enemy, and all else will follow” approach (Paul et al. 2016, 26). The counter-insurgency approaches used by Niger and Nigeria against the Islamic State of West Africa Province (ISWAP) fall in this approach (Berlingozzi and Stoddard 2020). On the other hand, the population-centric approach emphasizes that the primary task of counterinsurgency is establishing control over the population and the environment (physical, human, and informational) in which that population lives (Kilcullen 2006). The underlying philosophy is “First control the population, and all else will follow” (Kilcullen 2006, 17). Kenya has employed this approach in its fight against Al-Shabaab by focusing on community engagement to counter radicalization and insurgency influence (Finn et al. 2016).

This article hypothesized that the Government of Ethiopia’s counter-insurgency operation against the OLA followed an enemy-centric approach. The government’s publicly stated tactic of “drying the ocean to kill the fish” (as stated by Fekadu Tesema in 2022 in Oromia National Regional State Parliament address) summed up the regime’s approach to quelling the insurgency by clearing its civilian social base in which OLA lives and thrives. These draconian COIN operations resulted in large-scale displacement, economic disruption, and human rights violations in the area. What is even more striking is the invisibility of the disastrous consequences of the Government’s actions in the study area. In his latest address to the House of Peoples’ Representatives on October 28, 2025, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed unequivocally stated that Wollega was more devastated than Tigray, which received international outcry (Fana Television 2025). This statement corroborates what the ICRC (2025) who describes Oromia as a neglected crisis where civilians face lethal violence in the absence of both international headlines and adequate aid.

1.3. Methodology

The main aim of this study is to analyze and describe the features of the Ethiopian government’s COIN tactics and its catastrophic humanitarian impact. This is case study research which focuses on a specific socio-space: Wollega[1] and time (post-2018). The case study methodology is ideal for analyzing specific instances of counterinsurgency and its resultant displacement of people, offering insights into the unique dynamics and how military strategies influence population movements (Malkki 1995; Stake 1995; Oliver-Smith 2008).

Data was collected through a combination of tools and sources. Primary data was collected through interviews to capture firsthand accounts from the displaced and residents of the study area. Accordingly, semi-structured interviews were used to explore personal narratives and the socio-political effects of counterinsurgencies on individuals and communities. Due to the political instabilities and conflicts, an in-person interview was not feasible. Out of practical necessities, primary data was collected through telephone interviews with four (two women and two men) research participants[2], one from each of the four Wollega zones. After receiving the consent of the interview participants, the telephone interviews were recorded, transcribed, and thematically coded for analysis.

Furthermore, this study collected secondary data through archival research. Accordingly, governmental archives, non-governmental agency reports, and media reports were examined to understand how counter-insurgency tactics have developed and affected humanitarian outcomes. This involved document analysis, content analysis of media, and policy documents. Accordingly, secondary data was collected from the archives of Human Rights Watch, the United States State Department Annual Reports, the European Peace Institute (EPI), United Nations Office for Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), GoE’s press releases, Addis Standard (a local media outlet) and Reuters and The Economist (international media outlets). Since 2018:

-

Human Rights Watch produced five reports focusing on Ethiopia’s political violence, out of which two reports (2021 and 2022) paid attention to Western Oromia. The authors systematically reviewed these two reports and analyzed references to the counterinsurgency against OLA in Wollaga zones.

-

The United States State Department has published 4 annual state-of-the-country reports on Ethiopia. Out of these reports, reports published in 2021 and 2024 discussed the violence and displacements in Wollaga zones. The author has systematically reviewed these reports.

-

UNOCHA has published multiple reports on the political violence and displacements in western Oromia. The author reviewed two reports published in 2023 and 2024.

-

The Economist published one report (in 2020) that gave very good coverage to the conflict in Oromia. The report was analyzed.

-

Reuters published (in 2024) a special issue covering the counter-insurgency operation in Oromia. The report has been analyzed.

-

Addis Standard has published seven reportages focusing on the political violence, displacement, and humanitarian situation in western Oromia. The author has reviewed 4 out of the seven releases.

To make sense of GoE’s “scorched earth” counterinsurgency tactics and its devastating humanitarian impact, ‘necropolitics’ is used as the theoretical framework (Mbembe and Corcoran 2019, 19). Necropolitics refers to the use of power by the state or other actors to dictate who may live and who must die, extending to the management of life and death under conditions of oppression, occupation, and warfare. Necropolitical scorched earth tactic involves the deliberate destruction of resources, infrastructure, and livelihoods in areas suspected of harboring insurgents, thereby disrupting the insurgents’ support networks and forcing populations into submission or displacement. By viewing these tactics through the lens of necropolitics, we explored how the regime in Ethiopia assert sovereignty over populations by making life unsustainable in entire regions, effectively rendering certain areas uninhabitable. It is meant not only to decimate insurgent forces but also to punish and control civilian populations, who are often perceived as supporters or enablers of resistance.

2. Counterinsurgencies in Africa: State of Knowledge

Counter-insurgency in Africa has been a subject of considerable academic interest, given the continent’s prolonged conflicts and insurgency history. The roots of many African insurgencies (liberation movements) are mainly in the colonial era, when resistance movements were against the imposition of foreign rule and exploitation. Fanon argued that colonial psychological and socio-economic oppression fueled organized resistance movements for self-determination (Fanon 1963). Even after independence, many African states struggled with the legacy of colonial-era systems that failed to accommodate the diverse ethnic and political landscapes, delegitimizing the state in various groups’ eyes and prompting insurgencies (Mamdani 1996).

Counterinsurgency tactics used by African states are diverse. For instance, the Sudanese government utilized scorched earth tactics, particularly in oil-rich areas, to displace civilians and weaken the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA’s) support base (Johnson 2003; Rolandsen 2005). The government also mobilized ethnic-based militias like the Murahaleen and later the Janjaweed to fight the SPLA and terrorize southern Sudanese communities (Rolandsen 2005).

In Ethiopia, the Derg regime (1974-1991) targeted ethnic groups suspected of supporting insurgents, especially Tigrayans, Eritreans, and Oromos (Young 1997). It employed widespread torture, imprisonment, and mass killings as part of the “Red Terror” campaigns (Gedamu 2023; Tareke 2009; Young 1997). It also used counter-mobilization strategies whereby the regime recruited local militias from ethnic groups opposing the insurgencies to help fight rebel groups (Tareke 2009).

The Ugandan government under Yoweri Museveni launched repeated military operations (e.g., Operation Iron Fist) to destroy the Lord Resistance Army (LRA) camps in Uganda and South Sudan. The government forcibly displaced civilians into “protected villages” or internment camps, which often had poor living conditions, ostensibly cutting off the LRA’s access to food and recruits (Doom and Vlassenroot 1999; Finnström 2020).

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the government employed a range of counter-insurgency approaches and tactics in its fight against rebel groups such as the M23 (March 23 Movement) and the FDLR (Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda). These tactics reflect a mix of military, political, and diplomatic efforts. The DRC has conducted large-scale military operations against the M23, FDLR, and other rebel groups. For example, Operations “Sokola I” and “Sokola II” were significant campaigns launched by the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC) to clear rebel-controlled areas (Stearns 2012; Autesserre 2010). It also bolstered local militias (Mai-Mai groups) to fight against the rebel groups. However, this tactic backfired, as local militias had also engaged in illegal activities, contributing to further civilian displacements (Prunier 2008).

The conflict between the Malian government and the Tuareg rebels has been ongoing for decades, with periodic uprisings since Mali’s independence in 1960. The Tuareg insurgencies, particularly those in the 1990s and early 2000s and more recently in 2012, have been driven by the Tuareg’s demands for autonomy in the northern region of Mali, referred to as Azawad. The Malian government has historically responded to Tuareg rebellions with direct military force, deploying the Army to counter and suppress rebel activities in these regions (Lecocq 2010). The government also backed local militias to counter Tuareg insurgents, leading to complex inter-communal violence in northern Mali (Chauzal and van Damme 2015; Lecocq 2010). Another approach has been the systemic underdevelopment of its northern region, keeping the Tuareg marginalized and economically dependent on the central government (Chauzal and van Damme 2015), although this tactic has fueled long-term resentment and unrest. The Malian government also framed the insurgency as part of the global war on terror, a tactic that was used to gain international support and delegitimize the rebellion by conflating it with extremist groups like AQIM and Ansar Dine (Baldaro and Raineri 2020).

The Ethiopian regime’s use of violence as a COIN strategy has led to forced displacements of 794,000 civilians in Western Oromia (UNOCHA United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) 2024). These internally displaced people (IDPs) faced hunger, and malaria exacerbated the dire humanitarian situation (Addis Standard 2023a). This is significant because the Oromo in Wollega had never faced displacement or a humanitarian catastrophe before 2018. Furthermore, these brutal counter-insurgency operations were headed by politicians and military officers who claimed to have come from the same ethnic group as OLA and the displaced people.

3. Theoretical Framing: Necropolitics and Generalized Violence

A prominent official stated the Ethiopian government’s counter-insurgency tactics using the analogy of “drying the ocean to kill the fish,” a scorched earth tactic aimed at weeding out OLA by clearing its support base. This approach entailed civilian victimization, revealing the regime’s willingness to sacrifice civilian lives for political expediency. While some scholars argue about the situational effectiveness of civilian victimization as a counter-insurgency strategy (Downes 2007; Downes and Rangazas 2023), others critique the cost of such approaches on moral, legal, and practical grounds (Pape 1996; Horowitz and Reiter 2001).

To help frame what is happening to the people in Oromia, specifically in Wollega zones, this article draws insights from two key concepts: ‘necropolitics’ and ‘generalized violence.’ Generalized violence is the indiscriminate use of force to punish or control an entire community rather than specific individuals. It operates on the principle of collective punishment, where a group is targeted based on its identity—such as ethnicity, location, or political affiliation (Kalyvas 2006; Balcells and Stanton 2021). Tactics like massacres, forced displacement, and systematic destruction are employed to terrorize the population, break their will, coerce submission, or cleanse a territory. Beyond the immediate physical devastation, this approach inflicts deep collective trauma and is explicitly prohibited under international humanitarian law. On the other hand, Necropolitics is a concept that explains how governments (dictatorial regimes) and armed groups allied with them decide selectively who lives and who dies, using force to maintain control (Mbembe and Corcoran 2019). The necropolitical scorched earth operation demonstrates how regimes use death and suffering as political tools, manipulating life, death, and survival to maintain power. This can include the forced displacement of populations, the destruction of homes and agricultural land, the cutting off of humanitarian aid, and the imposition of conditions that lead to widespread starvation, disease, and violence. The use of these framings brings to light how such counterinsurgency approaches become instruments of both governance and terror, where the line between combatants and civilians is deliberately blurred, and entire populations face collective punishment.

Several actors at multiple levels were engaged in the counterinsurgency operation in the study area. To understand this multiple-actor theatre, this paper employs a multi-level analysis framework (e.g., Barcells and Justino 2014; Sirkeci 2009). At the macro level, the actors involved were the Ethiopian state and the Ethiopian National Defence Force (ENDF). At the mezzo level, the actors involved were the Oromia Regional State Police and Koree Nageenyaa (‘Security Committee’ in the Afaan Oromo language). The third level is micro. Actors at this level were Gaachana Sirnaa (Protectors of Regime, in Afaan Oromo) and the Amhara Fanno militia (Fanno for short). This paper will lay down the actions and roles of the actors at these different levels and how they interlace with each other to displace the population in Western Oromia.

4. Government of Ethiopia’s Counterinsurgency Operations in Wollega

4.1. The Insurgent: The Oromo Liberation Army

The Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) is an armed group operating in Ethiopia’s Oromia region. It emerged as the military wing of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), an organization founded in the 1970s to achieve self-determination for the Oromo people. It began its military operation against the Ethiopian state in eastern Oromia and gradually extended its operations to the Bale and Arssi areas and, in 1981, to Wollega (Jalata 1993).

Following the rise of Abiy Ahmed to the premiership in 2018, Ethiopia underwent a period of significant political liberalization, which included the legalization of previously banned opposition groups like the OLF. Many OLF leaders, including those in exile, were allowed to return to Ethiopia, and some engaged in the formal political process. Conflicts between GoE and OLA erupted after the reconciliation agreement reached in August 2018 between the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and the then Oromo Democratic Party (ODP) in Eritrea failed. Presumably, the agreement aimed to pave the way for the return of the OLF to Ethiopia, disarm its fighters, and engage in peaceful opposition politics. However, an organized disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) program did not occur, leading to the military wing of the OLF, OLA, returning to armed struggle to fight for the Oromo people’s right to self-determination. However, the conflicts in Oromia stem from more than the mismanaged disarmament agreement. The Ethiopian government’s century-old colonial approach to the management of Oromia was the root cause of the conflict in Oromia.

Since 2018, the OLA has expanded its insurgency, particularly in the western and southern parts of Oromia, including the Wollega zones. The group claims to defend the Oromo people against state oppression and marginalization, accusing the federal government of continuing the policies of exploitation that have historically disadvantaged the Oromo population. Its stated aim is to achieve self-determination for Oromia and protect Oromo interests. The OLA has been involved in a series of attacks on government forces and has also engaged in armed clashes with regional militias. It is known for its guerrilla warfare tactics, utilizing the difficult terrain of Oromia for hit-and-run operations. In response, the Ethiopian government has conducted military operations in western Oromia aimed at suppressing the group.

The OLA has been accused of human rights violations, including targeted killings, ethnic violence, and attacks on civilians. The Ethiopian government has labelled the OLA a terrorist organization and accuses it of engaging in ethnic-based massacres, particularly against Amhara civilians living in Oromia. Human rights groups, such as the Human Rights Watch, have alleged that OLA fighters were committing crimes against non-Oromo communities (Human Rights Watch 2022). For example, in late 2020 and 2021, there were reports of mass killings of Amhara civilians in areas of western Oromia, with local officials accusing the OLA of orchestrating the violence. This report highlighted the group’s involvement in ambushes, raids, and village attacks. However, the organization has repeatedly denied responsibility for these attacks, often blaming government-backed militias or other armed groups for the violence. The OLA claims that it only targets government forces and accuses the Ethiopian government of staging or facilitating some of the attacks to delegitimize the Oromo cause. The situation is further complicated by the presence of multiple armed groups in Oromia and the surrounding regions, making it challenging to verify responsibility for specific incidents of violence. In 2023, the European Peace Institute (EPI) released a report accusing OLA of human rights violations. The EPI had initially released reports suggesting that the OLA was responsible for ethnic violence and other human rights abuses in parts of Oromia, particularly in Wollega, where ethnic Amhara civilians were targeted (European Peace Institute 2023). These accusations led to widespread media coverage, contributing to a narrative that portrayed the OLA as responsible for atrocities in Wollega.

However, following feedback, including a detailed analysis from the OLA itself, the EIP acknowledged that the report had methodological flaws and that the claim was presented as an allegation rather than a confirmed fact. EIP formally apologized to the OLA, clarified that the OLA had denied responsibility, and agreed to stop further circulation of the report. The retraction came after new evidence suggested that the OLA may not have been involved in all the incidents as initially claimed or that the violence could have been perpetrated by other groups operating in the conflict zones. EPI acknowledged that its earlier reports lacked sufficient verification and expressed regret for the harm caused by the premature release of such information.

4.2. Counter-Insurgency Operation in Western Oromia: Multiple Actor Theatre

The post-2018 insurgency and counterinsurgency involved several actors at different levels: macro, mezzo, and micro.

4.2.1. Macro Level Actors

At the macro level, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed led the federal government, and the Ethiopian National Defence Forces (ENDF) were the key actors involved in the counter-insurgency operations in Wollega. From the birth of the modern state of Ethiopia in the late nineteenth century through internal colonialism, the continuation of historically asymmetric relations that sustained the empire had cemented deep-rooted state-society antagonisms and tensions. State violence was manifested in terms of economic exploitation, political oppression, cultural stigmatization, and the imposition of the language, religion, and culture of one ethnic group (that of the Amhara ethnic group) over Oromo and the others (Jalata 1999; Holcomb and Ibssa 1990).

Soon after coming to power in 2018, Abiy Ahmed’s administration began advocating for bringing the country back to its ‘Glorious Past,’ a period which, for the Oromo, was colonial suppression and humiliation (Jalata 2023b; Záhořík 2017). To the dismay of many observers, this call to return to the imperial era has been discursively and practically evident (Regassa 2021). Despite not changing the Constitution, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has used narratives with strong imperial resonances, confusing pro-federalist political forces, scholars, and observers of Ethiopian politics. Abiy’s significant political decisions were the dissolution of the multinational party, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), and the establishment of a unitary party, the Prosperity Party (PP), in October 2019. Ethiopianism, a nationalist sentiment towards Ethiopian identity, has always had support from a small fraction of Oromo elites, while the majority advocated for secessionism or federalism (Ostebo and Trovoll, 2020). The pre-2018 regime, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), had established an exploitative political economy and electoral authoritarianism, but at least provided a framework for self-government. The Oromo Protest from 2014 to 2018 was, in some respects, a push to strengthen Ethiopia’s multinational federal state system, ensuring that every nation and nationality of the country would benefit equally and enhancing Oromia’s autonomy. Despite its weaknesses, the constitutional establishment of Oromia as a regional state represented the Oromo and their aspirations for self-government.

In a stark detour from the pre-2018 political dispensation, the Prosperity Party’s manifesto does not allow for representation through ethnolinguistic affiliations. In a context like Ethiopia, where a single party presides over the government through electoral authoritarianism, there is no guarantee that the party will not reshape the state according to its ideology. This could result in the reversal of the multinational federation and the restructuring of the state along geographical boundaries to fit a unitarist administrative agenda. Thus, the ongoing war in Oromia is a struggle between the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) fighting for Oromo self-determination on the one side and the government countering this struggle. The violent counterinsurgency manifests the long-standing unresolved conflicts between those adhering to the imperial imagination and forces seeking to decolonize the Ethiopian state from it.

The federal government leaders’ imperial vision was evident in their discursive representation of the state based on selective historical memories. One example is the imperial palace, commonly known as the “Menelik Palace.” Constructed in 1890 after Menelik conquered much of today’s Southern Ethiopia, including Oromia, the palace has been a power center for successive regimes. It symbolizes a place of terror, torture, violence, and disappearance, where higher officials under the imperial and military regimes were executed, and hundreds were tortured under the EPRDF. Abiy renovated the palace, erecting statues of emperors Menelik and Haile Selassie. The associated narratives of a “return to the glorious past” were personified during the inauguration of the Adwa Museum project in Addis Ababa on February 11, 2024, at which time an Artificial Intelligence (AI) version of Emperor Menelik II gave a speech praising Abiy Ahmed for continuing his legacy.

These narratives informed the federal government’s decision to label OLA as a terrorist organization and mobilize all available forces to destroy it. In May 2021, the Ethiopian government officially designated the OLA as a terrorist organization, but it has not been shared by the United States of America (USA), the United Nations (UN), the United Kingdom (UK), or the European Union (EU) (The Economist 2020). This designation led to the mix-up of counterinsurgency with counter-terrorism approaches, with the government’s operation characterized more by the latter. After the terrorist label, the government declared a state of emergency in Western Oromia from November 2021 to November 2022, effectively placing Wollega under military rule and restricting civilian mobility, their access to telephone and internet services and humanitarian assistance.

The other key macro actor involved in the counterinsurgency operation is the Ethiopian National Defence Force (ENDF). The ENDF is ranked fifth in Africa, comprising Ground Forces, Air Force, and Naval Force (Global Fire Power 2024). The Ground Forces have four regional commands: Northern, Eastern, Western, and Southern Commands. In a bid to quash the OLA and its support base, the Western Command has been mandated with de facto and de jure emergency powers to govern over the Wollega zones. The US State Department of State Report (2024) documented that since the onset of the conflict, Wollega zones have been administered through the mandate of militarized Command Posts, whether or not State of Emergency (SoE) legislation was in force. It exemplifies the logic of necropolitics as it is evident that the Ethiopian state mobilized massive force to dictate who may live and who must die.

4.2.2. Mezzo-level Actors: Oromia Regional State Police and Koree Nageenyaa

At the Oromia National Regional State level, counter-insurgency operation was guided by the belief that since Prime Minister Abiy hails from an Oromo ethnic group, no Oromo opposition against his regime should be tolerated in his home state of Oromia. Milkessa (2022), a former senior government official in Oromia noted:

In late 2018, Prime Minister Abiy admired how the TPLF ruled Tigray without opposition for 27 years (1991-2018). He asserted that the Oromo Democratic Party (ODP) [PP] should rule Oromia similarly. Abiy aimed to rule Oromia with an iron fist, silencing all opposition, particularly those supporting multinational federalism and decentralization of state power.

Abiy Ahmed and his regime identified Wollega as the main source of opposition to its rule. Since coming to power, Abiy Ahmed’s first air strikes, drone attacks, and massive military mobilizations were in Wollega (The Economist 2020; Oromia Support Group 2025; Oromia Support Group–Australia 2025).

Mezzo-level actors that were involved in the counterinsurgency were the Oromia Regional State Police and Koree Nagenyaa, both deployed with a mission to wipe out OLA and its supporters. A statement by Fekadu Tesema, a senior government official, encapsulates the regime’s approach toward citizens in Wollega:

Some of you [parliamentarians] have been asking why we failed to win against Shane [Oromo Liberation Army] after we defeated the Junta [Tigray Defence Forces]. You should understand the difference between conventional war and guerrilla fighters. In conventional wars, fighters equipped with heavy machines face each other in battles. What we experienced in Northern Ethiopia against the Junta [TPLF] was a conventional war. The guerrilla (OLA) fights differently. They (OLA) get logistics from the community. During the day, they live as civilians with the people. They even attend community meetings. They get information and communications by living abreast of the community. They know who is saying and doing what. In the evenings, they act against our political leaders and military. It is very complex and difficult. The way to eradicate Shane is the same as how to get rid of fish from the Pacific or Indian Ocean. It is impossible to pick out all fish from the ocean. If you want to completely get rid of the fish, you need to dry up the ocean (Tesema 2022).

The analogy of “drying the ocean to kill the fish” epitomized a strategy of indiscriminate and collective punishment, wherein civilian populations are targeted to quell an insurgency, regardless of their involvement. This approach exemplified the regime’s willingness to sacrifice civilian lives for political expediency. While some scholars argue about the situational effectiveness of civilian victimization as a counter-insurgency strategy (Downes 2007; Downes and Rangazas 2023), others critique the cost of such approaches on moral, legal, and practical grounds (Pape 1996; Horowitz and Reiter 2001).

Koree Nageenyaa carried out several indiscriminate attacks on civilians in Wollega zones. This secretive security apparatus began operating in the months after Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed came to power in 2018. Through landmark investigative research, Reuters documented how it had carried out extrajudicial killings, illegal detentions, and destruction of homes and properties, all to crush the OLA insurgency (2024). In 2021, this security apparatus publicly executed a 17-year-old teen in Dembi-Dollo town, the capital of Kellem Wollega Zone. According to our interviewee, Gadisa Dembeli:

On May 11, 2021, government forces apprehended and beat Amanuel in Dembi Dollo town. His parents, siblings and relatives watched helplessly as armed security people beat him mercilessly. They taunted a bloodied Amanuel with a handgun tied around his neck. He was executed in public that day while his family was crying out for mercy. (Dembeli 2023)

The actions of Koree Nageenyaa created a death world- a state of social existence in which civilians, urban and rural dwellers alike in Wollega were subjected to such an abject living condition that rendered them unfree, living under a draconian military command rule, and perpetually displaced.

4.2.3. Micro-level Actors: Gaachana Sirnaa and Fanno

At the micro level, this article discusses the roles played by Gaachana Sirnaa and Fanno. Fanno, a paramilitary group from the Amhara ethnic group, operated alongside the state and has been implicated in numerous human rights abuses in Wollega (Milkessa 2024; Abeshu 2023). Fanno supported the Prime Minister’s zeal for taking Ethiopia back to its imperial past, a period in history ruled by Amhara elites.

A major ‘local’ actor that threatens the life and security of people in the East Wollega and Horo Guduru Wollega zones of Ethiopia is the Fano, an Amhara armed group that has expanded into Western Oromia from its main base in the Amhara region. Fano’s operation in these areas is driven by an expansionist ideology. Since 2018, Amhara elites have constructed and promoted the narrative of ‘Greater Amhara’ (Ermiyas 2022), which seeks to annex territories from neighbouring regional states. This includes claims over areas such as Metekel in Benishangul Gumuz, Wollega and Dharra in Oromia, and Walkayt and Raya in Tigray, as well as the capital city, Finfinne (Addis Abeba) (Ezega News 2020; Abeshu 2023; Regasa and Abeshu 2025). Amhara elites, including Fano leadership, argue that Wollega was historically Amhara land before the Oromo settled in the area. This imperial and expansionist narrative resurfaced following the 2018 rise to power of Abiy Ahmed and his political vision of restoring “Greater Ethiopia” (Lefort 2020).

This ideology is explicitly articulated by its proponents. Major Dawit Woldegiorgis, a former senior government official during the Derg regime and a leader of the Amhara National Movement (ANM), claimed:

Wollega used to belong to the Amharas. In addition to Wollega, I believe that Amhara Fano will also reclaim all the territories that used to belong to Amhara but are currently occupied by the Oromo (Woldegiorgis 2021).

Since 2019, Fanno has been involved in targeted attacks on civilians, burning houses and evicting people from their homes and farms, and looting cattle and grains (Oromia Support Group 2025; Oromia Support Group–Australia 2025). Focusing on East Wollega, Horo Guduru Wollega, West Wollega, and Qellem (Kellem) Wollega, the Oromia Support Group–Australia (OSG) reports that Amhara “Fano” militias have carried out repeated attacks particularly in East Wollega and Horo Guduru Wollega—incursions OSG characterizes as targeted violence against Oromo civilians involving killings, village burnings, looting, abductions, and large-scale displacement. OSG’s submission describes patterns of raids across district lines and from neighboring areas, noting cycles of reprisal that have devastated rural kebeles, disrupted farming, and driven residents to flee to towns or IDP sites. In West Wollega and Qellem Wollega, OSG documents similarly grave incidents amid multi-actor fighting; while control of territory and the mix of armed actors vary over time, OSG attributes a number of killings and forced displacement episodes in these zones to Fano-linked units operating alongside or parallel to other forces. Overall, OSG portrays a deteriorating security environment across all four Wollega zones in 2023–2024 in which Fano militias’ actions—especially in East Wollega and Horo Guduru Wollega—have been a significant driver of civilian harm and displacement (Oromia Support Group–Australia 2025, 6–8). Interviews conducted also corroborate the OSG report. For instance, according to Lamessa, the following were attacks carried out in Jidda Ayana and Kiremu districts in East Wollega zones:

On 13 February 2021, 14 people were killed in Andode Dicho, Ali, and Dooro Oborra Kebeles, their livestock was driven away, and houses were burnt down. On November 29, 2022, another indiscriminate killing took place in Kiremu District. Fanno killed more than 20 people, including Kiremu District First Instance Court judge, Mr. Damtew Gemeda. And, on December 3, 2022, Fano killed 69 Oromo in Gutin. This includes Dr. Hassan Yusuf’s Family. Dr. Hassan is the President of Wollega University (Lamessa 2024).

These narratives also build on decades-old demands by local Amhara migrant settlers in Wollega for a special status, such as a special zone for Amhara communities in Western Oromia.

Fano’s actions mirror historical parallels with similar ideologies that have fueled conflicts globally. For instance, in Serbia, nationalist myths were used to justify Slobodan Milošević’s pursuit of a “Greater Serbia,” which aimed to unite all Serbs by annexing territories from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Kosovo (Baker 2015; Glenny 1996). This ideology fueled ethnic cleansing, including the 1995 Srebrenica genocide (Baker 2015; Glenny 1996). In Sudan, the Janjaweed militia, driven by a belief in Arab supremacy, carried out mass killings in Darfur (Mamdani 2009; Prunier 2005). In both instances, elites justified territorial expansion through violent force, cloaked in claims of historical right and ethnic superiority.

The relationship between the Ethiopian government (GoE) and Fano has been complex and has swayed between collaboration and conflict. Initially, the Ethiopian government supported and armed Fano during the war in Tigray. It also used the group to fight the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), aiming to reduce civilian reliance on state security forces. Between 2019 and 2023, these two actors fought side by side against the OLA and the Tigray Defence Forces (TDF). However, the relationship has soured, and since September 2023, Fano and the government have been fighting each other for control of central state power. Fano has increasingly pursued its own goals, culminating in the formation of what came to be known as the ‘Wallega (Bizamo) Fano Command’ in December 2024.

On the ground, the Fano operates in coordination and alliance with locally organized Amhara militia, most of whom were born and grew up in the region, and some moved to the areas in the last couple of years. Due to the government’s interest in using these groups against the OLA, local Amhara farmers were partly armed by the Oromia Regional State, while others bought firearms and were tolerated from being disarmed, unlike the measures taken against Oromo inhabitants. Furthermore, reports also indicate that the attacks by Amhara militias are not isolated and localized incidents; rather, they are part of Amhara forces, including the Amhara regional government’s displeasure with the federal government’s agreement with Tigray.

In addition to Fanno, at the local level, victims of attacks in the study area accused Gaachana Sirnaa as the perpetrator of atrocities and attacks on community members accused of supporting or sympathizing with OLA. Abuune Dajanee, an interviewee, spoke about the brutal actions of Gaachana Sirnaa:

The gunshots were unbearable, so we fled to save our lives. It was a nightmare and very difficult for my children. We lost everything and have not received any assistance since we arrived in Balo. No one has come to ask about our situation (Abuune 2024).

Part of the Gaachana Sirnaa were also tasked with shadowing and acting like OLA. A former Prosperity Party government official, Brigadier General Kemal Gelchu, who was the head of the Oromia Regional State Security Bureau, stated that the government formed Gaachana Sirnaa to impersonate OLA (Oromia Global Forum 2020). Several of these atrocious crimes were blamed on OLA, an accusation which even the state-affiliated Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) dismissed (2023).

Beginning in 2024, farmers in the study area were being forced to undergo militia training against their will to obtain fertilizers and pesticides, and those who refused were subjected to arrests and torture. One of our interviewees, Abune Dajanee, a resident of Haroo Bulluq District in Horroo Guduruu Wollega region, said her 24-year-old son was forcibly taken to Shambu town in March 2024 for training. After completing it, he was assigned to join the operation against OLA. Abune, a mother of seven and a displaced elderly needed her children’s support to get through the day. With the relocation of her son, even basic activities such as cooking and cleaning had become very hard for her. The research participants’ responses revealed that the combined effect of the forces at the macro, mezzo, and micro levels has devastated the civilian populations’ lives and livelihoods.

4.3. Humanitarian Impact of Counter-Insurgency Operations: the Necropolitics of Death and Displacements

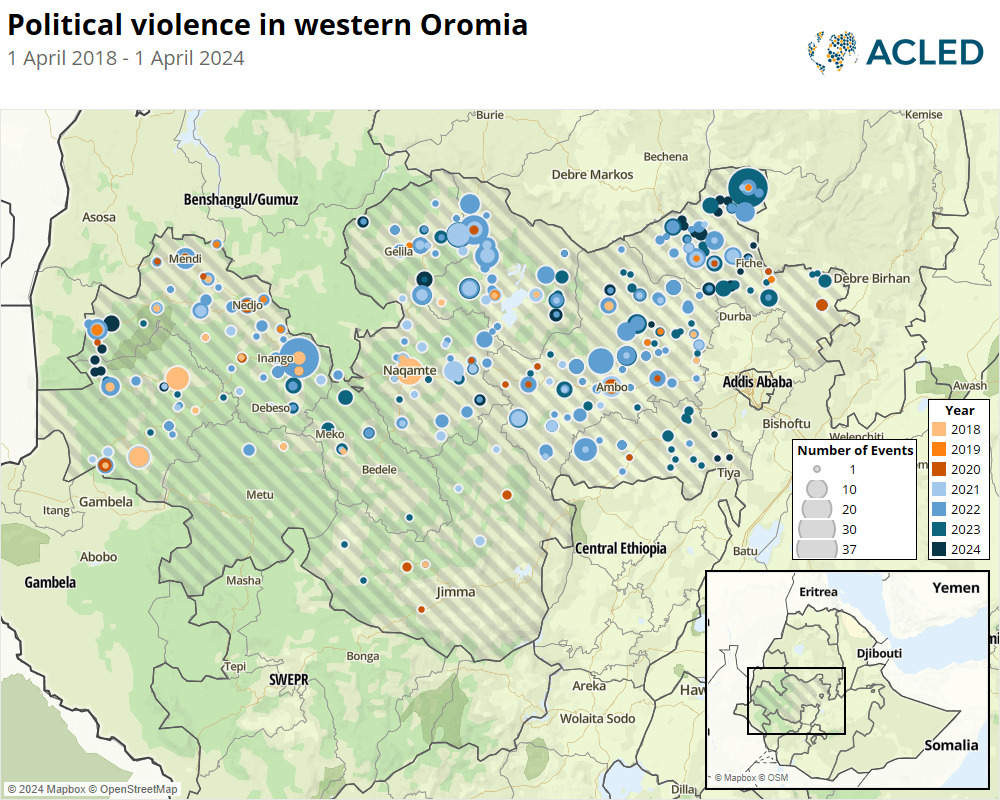

Since the re-ignition of GoE’s attack in 2018, Wollega has been devastated. To subdue the OLA operation, various actors were mobilized, displacing 794,000 in the study area, most of whom lacked adequate humanitarian assistance (UNOCHA 2024; US State Department 2024). Figure 1 shows a map of the violence in Western Oromia.

Furthermore, the toll of the COIN on human lives was immense. One of our interview participants, Amina Hayu, who witnessed ENDF soldiers and Oromia Police setting fire to her home in Nura Humba Kebele of Nunu Kumba District, noted:

Members of the Oromia police, Gaacha Sirnaa, and soldiers [ENDF] burnt my house. They came and set fire to my house around noon. They did not give us any prior notice or information. They burnt my grass-thatched house. They lobbed a flame at the roof. They only burnt my house out of many in the neighborhood. In our Kebele, they also burnt houses belonging to others. The soldiers burnt selected houses belonging to people suspected of supporting OLA.

The recently released US State Department Human Rights report noted that the Government of Ethiopia’s counterinsurgency campaigns against OLA involved unlawful killings of civilians (2024). Furthermore, the COIN operation destroyed private and public properties such as residential houses, schools, hospitals, and other vital public service infrastructures (Addis Standard 2023b). This is necropolitics at its best: the totality of forces deployed to determine whose lives and livelihoods were taken and whose were spared. Our third interviewee, Abdisa Lamessa, noted that residents of 18 out of 19 villages of Kiramu District in East Wollega were displaced and were sheltered inside Kokofe Elementary School, in Gida Ayana and Kiramu Elementary School before they were made to evacuate days before the start of the 2023 Ethiopian academic year.

Beyond attacks on civilian lives, the Government’s counterinsurgency measures did not spare critical infrastructures. The UNOCHA report (2024) highlighted how the Government’s ongoing operation in the study area had seriously destroyed health facilities and water systems. For instance, in Begi, a district of 100,000 inhabitants, nearly all forty-two existing health posts have been destroyed. Patients with life-threatening medical conditions cannot receive urgent care because health facilities are no longer functioning. Similarly, Abdisa, an interviewee, spoke about the situation in his district of Guduru:

The walls of the Guduru Primary Hospital, which serves more than five districts, were riddled with bullets, and its water tank was damaged. Beds, equipment, surgical sets, medicines, and ambulances were looted. At the same time, the number of patients has drastically increased as thousands of people who fled their homes arrived in this area, making it extremely difficult for staff to provide healthcare services to the population.

In addition to the killings and destruction of infrastructure and livelihoods, the displaced people often found it challenging to access humanitarian assistance. Due to insecurity, the majority of these IDPs in the four zones of Wollega have generally not received the humanitarian aid they need. The US State Department report indicated that “access to western Oromia was extremely restricted, imposing constraints on medical facilities and limitations on humanitarian access” (2024, 16). Two layers can be peeled from this. First, patients with life-threatening medical conditions cannot receive urgent care because health facilities are no longer functioning. Secondly, aid (including food and medical assistance) was not allowed to reach the IDPs as the government alleges that the people are found in ‘rebel zones’ (Addis Standard 2023b). The net effect of these tactics has been that the people suffered under the counter-insurgency-counter-terrorism approach that aimed to ‘dry the ocean to kill the fish’, as Fekadu Tesema, a government official, lamented.

The denial of access to urgently needed humanitarian assistance can partly be explained by the fact that national states carry out the status designation and management of internally displaced persons. Despite the United Nations defining IDPs as a humanitarian policy concern, internal displacement falls within states’ jurisdiction because humanitarian actors perceive IDPs as within the reach of their government. Consequently, much of the designation and humanitarian service provision is at the mercy of the Ethiopian state.

GoE’s counter-insurgency operations have led to grave and systematic violations of national and international laws. For instance, the International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia documented mass killings, rape, starvation, forced displacement, and arbitrary detention (US State Department Report 2024). These atrocities became possible because Wollega had been administered through the mandate of militarized command posts before and after the State of Emergency legislation. This shows the systematic nature of the actions of necropolitical Ethiopian states and their allies in crimes. Necropolitical states deploy their force to define who is disposable and who is not. In contemporary Wollega, populations that the regime deemed were opposing its rule are singled out for brutal attacks by the multitude of state and non-state security actors.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the root causes of the conflict and instability in the region can be traced to three intertwined sources. Firstly, the Ethiopian government’s desire to maintain and widen the colonial-era social hierarchy is a primary factor. The government perceives the Oromo people’s political aspirations, particularly their pursuit of self-determination and self-rule, as anti-Ethiopian due to their potential threat to the established power structure. Secondly, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed’s pursuit to consolidate and strengthen his political power is another significant contributing factor. The third reason is that the Ethiopian government’s long history of using violence to suppress the Oromo people and manage the situation in Oromia was the leading cause of the conflict with the OLA.

Since 2018, several actors located at different levels have been involved in the COIN operations. The Ethiopian Federal Government and the National Defence Forces (ENDF) were involved at the macro level. At the mezzo level, Oromia Regional State Police and Koree Nageenyaa were involved. Moreover, at the micro level, Gaachana Sirnaa and Fanno were the main actors accused of displacing civilians. One of the key features of this counterinsurgency mobilization was the marriage of convenience between these state and non-state actors. While these actors have differing motives and capabilities, their singularly shared goal/denominator has been the aim to subdue the Oromo Liberation Army at all costs- including at the expense of civilian victimization.

The COIN tactics of the Ethiopian government and its allies have been “drying the ocean to kill the fish” – an indiscriminate and collective punishment wherein civilian populations are targeted to quell an insurgency, regardless of their involvement. This approach exemplified the regime’s willingness to sacrifice civilian lives for political expediency. In the literature, the enemy-centric counterinsurgency approach has been discussed mainly about organizations labelled as ‘terrorists’. In the case at hand, the population residing in the OLA stronghold has been subjected to the destruction of livelihoods and infrastructures and the denial of access to adequate humanitarian assistance. These government actions speak to the defining features of necropolitical regimes that deploy the totality of their power toward defining and assigning value (or not) to human life. The authors of this article hypothesize that given the failure of the necropolitical enemy-centric counter-insurgency approach, readers shouldn’t be surprised if the GoE resorts to discourses of a population-centric COIN approach to win over the hearts and minds of the civilians in the study area.

Ultimately, the silence surrounding the atrocities in Wollega serves as a harrowing indictment of the current humanitarian order. The disparity in the national, regional (IGAD, AU) and global response is not merely a logistical failure but a moral one, reinforced by an implicit hierarchy of suffering (Farmer 2003) that privileges victims in geopolitically strategic regions while rendering the Oromo civilians of western Ethiopia invisible. As mass displacement and violence in Wollega continue unabated yet underreported, the situation epitomizes the modern neglected crisis (Norwegian Refugee Council 2025), a catastrophe where the severity of human need is inversely proportional to international attention. To change this systemic inequity, the international community must shift its focus from political expediency to a universal standard of human dignity. Only by challenging these entrenched valuations of life can we move toward a framework where aid is distributed according to necessity rather than media visibility, ensuring that populations like those in Wollega are no longer left to languish in the shadows of global indifference.

The authors would like to underline that the OLA operation and the Government of Ethiopia’s counter-insurgency operation are Oromia-wide.

For the sake of the security and safety of the research participants, the names of the research participants have been anonymized and replaced with pseudonyms.